What the heck?

Wednesday

[Note: section two of this post has been edited since I first put it up this morning.]

[Note 2: and it’s been edited a second time.]

1.

So the exercise plan that I came up with on Tuesday was to start rising at five a.m. daily. On the first day I would go to the gym and lift weights for arms and chest, then use the gerbil stepper. On the next day, I would go to the gym and lift weights for back and shoulders, then go for a run. On the third day, I would go to the gym and lift weights for legs and abdominal muscles, then use the gerbil stepper. On the fourth day, the pattern would start over.

But the Y, I discovered Wednesday morning after heaving myself out of bed, still exhausted after a rather poor night’s sleep and hung over from a bedtime Benadryl, doesn’t open until 5:30. (I can’t escape the feeling that there is something wrong with you when you are getting going earlier than the Y, but I never claimed to be completely sane, especially not under the current circumstances.) So I went for a run (otherwise it would have been a gerbil stepper day) even though I had also run on Tuesday. Just as well, because I was eager to try out the new shoes I purchased on Tuesday, which I also figured would save me from a little of the strain that two days of running in a row would put on my semi-untrained muscles and joints. And the shoes (some variety of New Balance) were, um, great (not sure what to say about shoes, really). By the time I was done, the Y was open and I nipped in for said arms and chest exercises, and life was back on track.

2.

Over breakfast I read of the first of the funerals for the victims of last week’s rowhouse fire. Authorities are saying that the fire seems to have been caused by someone falling asleep while smoking on the living-room couch used as a bed. I have always heard that a couch can be a real fire-bomb, especially because of the way an ember can sink into the foam and smolder even after it looks like you’ve brushed it off. In fact, if you ever do drop an ember of any kind on a couch, and there is any chance that this may have happened (i.e., the couch cover has a hole burned in it), I’ve heard that you should put the affected cushion outside overnight just to be on the safe side.

Meanwhile, smoking in bed? Who does that? Maybe the problem is that, with fewer and fewer people smoking, the public safety messages these days all tell us simply not to smoke, as opposed to the little reminders they used to tuck into movie previews and radio announcements and even songs specifically warning against or at least alluding to the dangers of smoking in bed. The concept was drilled into me at about the age of eight or nine when an apartment in our complex burned and my father explained that this had been the cause. He of course grew up in the era of omnipresent cigarettes and so had been pretty well trained concerning this danger himself. The smoker in this case died, I think, or I assumed he did, and the blackened hole of his apartment was a daily reminder of the risk. So don’t smoke, but if you must, never do it unless you have at least one foot on the floor. Or is that the rule for how teenagers have to sit on the couch in the basement with their dates?

All joking aside, the article about the funeral was devastating. Apparently, all but one of the fire’s victims were related, and that one was essentially an adopted member of this free-form, self-defined family of a type that is so typical of America’s urban poor, carrying on traditions of self-sufficiency and survival against terrible odds that began during slave times (so don’t believe this nonsense about there being no functioning families in the ghetto, it’s society that isn’t functioning, at least at this level). The family had hoped to bury all seven victims at once, but they must first wait until each victim, most of them apparently charred beyond recognition, has been identified. (You know, so they’ll know which one is in which grave.)

But identifying each victim is taking longer than expected because no dental records are available.

Because not a single one had ever been to a dentist.

Tuesday’s funeral was for seven-year-old MarQuis Ellis, known as a friendly, smiling child who enjoyed riding his bike and playing tag and who met his end like the rest of them, alone and afraid in a hellstorm of smoke and fire. It’s almost more than I can bear to think about this and keep typing, but I wanted to mention the strange and disturbing eulogy given by Reverend H. Walden Wilson II, of Israel Baptist, who seems to have essentially taken the tack of telling the mourners to be glad the boy died.

The good reverend, as quoted in the Sun:

“No Christian would want to live… in this life, in this city, in these neighborhoods, with all of the imperfections. Who wants to live here forever?

“I can speak on behalf of MarQuis… he will never experience any childhood diseases. He will never encounter any gang violence. He will never experience cruel and evil speech. He will never experience drug activity… A young boy. Seven years old. Already experienced victory.”

The reporter paraphrased the reverend further:

“Marquis’s death, said Wilson, is a victory for a boy who will never have to ride his bike down dangerous streets again or worry about his mother braiding his hair.”

I guess this is the style of a certain kind of religious outlook, “the world is not my home, I’m just a-passing through” (a song about which I agree with Woodie Guthrie). And I know that the reverend intended only to console. But I found myself reading his words with a growing sense of anger that I can’t quite explain. Maybe it’s anger at the hopelessness expressed in this view, the way this view helps people accept the injustices done to them, as if the more injustice you can bear, the godlier you are, which may be, but it also coincidentally benefits the people actually responsible for the injustice. (Which, not to bring you down or anything, is pretty much all of us who can sleep at night while the MarQuises of the world bed down in dilapidated firetraps and reach the age of seven without once receiving some of the most basic medical care.) Or maybe it’s anger that some members of this so-called society experience so much injustice that they need this outlook just to get through each day.

But also, think of the attitude toward life you would need to have to find comfort in such words. I won’t be so arrogant as to claim that I can speak for MarQuis, but I’m guessing that, if we could have asked him, he might have been willing to endure some of the travails the reverend described if it also meant he could have experienced his first kiss, seen the sun rise over the ocean, gone to college (unlikely, in a city where less than a third of African-American adults even have a high school diploma, but you never know), maybe gotten married, maybe dropped off MarQuis, Jr. for his first day of school, maybe cured cancer. You just never know.

MarQuis seems to have struck a chord, at least: hundreds of friends, family and strangers attended his funeral, including preachers from both the west and east sides, which means a lot in this divided city.

3.

Back at work, back to the grind. The end is in sight but quite far off, really, which leads to what I’ll call some perception problems, as if I’m constantly switching back and forth between a telescope and a microscope. At lunchtime I walked to Safeway for a new jug of water. This Safeway has recently gone “upscale,” meaning fake hardwood floors in the produce section (like Whole Foods, I guess), special tilted display shelves at the ends of the aisles, tons more managerial-looking employees who lunge at you and ask how you’re doing every time you turn around, and unappealing little seating areas inside and outside the store that it’s hard to believe they really want anyone using. And who wants to sit and eat either in a converted aisle under flourescent lights, nowhere near a window, or outside next to the parking lot where you will be hassled by all of the people who want to sell you their food stamps?

Another innovation: small little European-style carts with two little cargo baskets, not much bigger than hand baskets, stacked atop each other, with no seat for kids. I was entering the store behind one woman who was slowly wrestling one of these into the store with one hand while she held a cell phone to her ear with the other, trailed by a toddler clutching her pants leg. The toddler appeared barely able to walk upright without support; she came up to maybe the woman’s knee. As the woman made her glacial way into the store, the toddler realized that she was not going to get to ride in the cart and began bawling.

“You hear her?” the woman chuckled into her phone. “She pulling on me and yelling.”

Finally, I saw a small opening and plunged past them.

“Yeah, well, she can’t always get what she wants,” I heard the woman continue into her phone. “She got to learn some day.”

I could hear the screaming and increasingly hoarse child the entire time I was in the store.

Wedding Attire

I was upbraided by one reader for not reporting what the bride and flower girl wore. Fortunately, there is an extensive photographic record I could refer back to.

They seem to have worn dresses.

(Actually, if you go and look at Diane’s comment, you’ll see I essentially stole her joke.)

Bird Camp Update Coming Soon

Sorry it’s been so long. Expect a new one in the next day or two.

Tuesday

I got home from New Orleans on Monday night but had cleverly taken Tuesday off as well, as a decompression/get-my-head-on-straight day. Throughout the early spring, I had looked at the New Orleans trip as marking a boundary between the period of time when I could just dabble in getting ready for the move, and the period of time when preparations would have to begin in earnest. In addition to unpacking, then, I knew that I would need to sit and do some planning, make a few calls, etc., before returning to giving my best eight hours of each day to someone else. Well, not giving, but you know what I mean.

So I was up by eight a.m. and headed to the gym. This will be a difficult summer, I think, with ample opportunities for visits from the black dog, so I want to get into a real exercise routine to keep my mood and energy up. Routines in general are reassuring to me, in part because it’s the best way to make sure I get the important things done, but also there is just something soothing about knowing what shape my day will take, if only in outline. Don’t worry, this won’t become an exercise blog (I don’t consider it a blog at all; blog is short for weblog, which originally meant “log of interesting stuff you found on the web,” but I guess that’s a usage battle that is pretty much lost), but it finally occurred to me that I could overcome my hatred of lifting weights in a gym by breaking up my routine, and then, on alternate days, running and using the elliptical trainer. I know, I know, that’s what everyone does. It just hadn’t clicked into place for me before in a way that felt manageable.

So I moved some heavy objects and then went for a run. The cupboard, as I believe I mentioned, was bare, so I went to Sam’s for bagels for my brother and me, and was at my desk working on the final diary entries from New Orleans/Baton Rouge by eleven or so. I emailed the property manager and our alleged future tenants, and I filled out a form on a moving company’s web site so that they can call me with an estimate. This is the same moving company that moved my parents to West Virginia, and my parents raved about them, not least because they were inexpensive. The company seems to act like it wants your business, and that’s my favorite kind.

I also uploaded the New Orleans/Baton Rouge photos to Flickr, a process that has become so amazingly fast and easy now that I have a computer with decent memory capacity. Not that they’re paying me or anything, but I highly recommend Flickr for your online photo sharing (I especially recommend it if you want to share them with me – I ain’t looking at no Snapfish), not least because no one has to join Flickr to see your photos. Even if you keep them “private,” which you can do at various levels of restriction, you can use a “share” function to grant access to anyone with an email address. And why keep them private, unless they are risque? I know people are often very concerned about pictures of their children ending up on line, but I’ve never understood why. Maybe it’s because there is this steady drumbeat in the culture about online predators, but those people are in chat rooms looking for real people to converse with. Of course you need to be careful about giving out too much information, so it might not be a good idea to post pictures in which your address is visible or your house is otherwise locatable, particularly if you also post pictures of the riches contained in your treasure room. But even then, what are the odds that a burglar is out there scouting around on line for places to rob? I suppose it could happen, but that kind of burglar really will be looking for a treasure room, not a tiny rowhouse that contains pretty much the same stuff as any other tiny rowhouse.

Except for my shrunken head collection, of course.

And back to Flickr, for a second. The best thing about Flickr is that it is very easy to navigate and use. The second best thing is that the color scheme is reminiscent of a box of laundry detergent, and doesn’t that just make you feel clean and happy?

By late afternoon I was already feeling very productive, and it didn’t stop there. After starting some laundry, I drove to Fells Point to get a new pair of running shoes and then stopped by Giant for some groceries. I guess one reason I was able to get so much done is because of the feeling I always get when I’m home on a weekday – even on a vacation day that I earned fair and square – that I am somehow playing hooky, yet another example of the way our minds are poisoned by this innocent-sounding thing called a work ethic. Frankly I wish I had a stronger leisure ethic, but that’s a rant for another time. But the idea that I “should” be working anyway makes it harder to laze around like I might end up doing on a Saturday.

In other news, while I was at Giant, I received live text-message updates from my brother concerning the car that crashed into the outdoor-seating area at Regi’s, the bistro where I once tended bar (my brother works across the street). Amazing that more people weren’t hurt, and that the ones who were got off so lightly. Just think, if I’d kept working there for only three more years, and if I’d happened to be working a wait shift last night, and if I’d happened to have been standing in the outdoor seating area taking an order… well, the mind quails.

That’s all.

The Big Easy Wedding, pt. 5

The morning was no fun. We were both tired and reluctant to rise, because of said tiredness and also because rising meant packing and saying goodbye. But A.’s airport shuttle would leave at seven and we eventually accepted the inevitable. While we gathered her things, I turned on NPR on the radio. I did this with a certain amount of trepidation, since I hadn’t really followed any news since leaving Baltimore. What had I missed? A local politician was being interviewed about Louisiana’s impending cockfighting ban. There was “mysterious bubbling” in a lake in the northern part of the state. Some bombs had exploded, and some people had died.

A. and I said goodbye at the door to the room and I watched her walk away down the hall, her duffle bag slung over one shoulder. The only thing for it was to keep busy, so I finished my own packing and did a little typing before checking out at eleven and locating our friend, Tracy, who was coincidentally on the same flight as me. For some reason, we had both arranged to depart from the New Orleans airport rather than Baton Rouge’s, and we had decided to join forces in figuring out how to get down there. A cab ride would cost $130, I had learned from guest services, so that was out. The night before, I had reserved a car from Thrifty; with taxes and “drop fee,” the drive would cost us only about $65. Thinking I might want to spend the day sitting in the hotel typing up my last notes from the weekend, I had ordered the car for two p.m., but Tracy convinced me that we should get it early and maybe knock around the French Quarter for a couple of hours. (Our flight was at six p.m.) So we caught the eleven a.m. airport shuttle. At Thrifty, they didn’t have any cars of the size I had ordered (economy). If they hadn’t had any at two p.m., the upgrade would have been on their dime. But since we were requesting the car early, we had to pay an extra $14 for a PT Cruiser convertible, which – surprisingly – was the cheapest rental they had on the lot. Since the only other option at that point was to sit in the Thrifty waiting area until two p.m., we decided to go for it.

We studied the driver’s manual for instructions related to the convertible top before leaving the rental lot. Not exactly rock and roll of us, I know, but then, neither are our bank accounts. Mainly I wanted to know if you could put the top up and down while moving, as it looked as though it might rain. (You can’t.) There was a ZZ Topp Memorial Day rock block on a radio station we found and we were blasting the rumbling instrumental bridge of “La Grange” as I accelerated onto the main road. I had visions of booming along the Lake Ponchartrain levy with the top down, but I couldn’t take the sun beating down on my sparsely forested skull after about 15 minutes and gave up. Tragedy was narrowly averted, too, when we stopped at a drug store for some cortizone for Tracy, who must have brushed some poison ivy on Sunday’s bayou stroll. We were just pulling out of our parking spot when a warning ding sounded; a little readout flashed “deck.” I had no idea what this could mean, but after a few fruitless minutes with the owner’s manual I decided to check the trunk. It was ajar, and a chill ran down my spine. An open trunk on a sedan is no big deal, but a PT Cruiser convertible’s trunk is accessed through a vertical opening in the back of the car, meaning that – if it is open – there is nothing but a little lip to keep the contents from sliding right out the back, like jeeps being parachuted out of the ramps in the rear of those massive Air Force cargo planes. I remembered closing and checking the trunk at the rental lot. Had someone popped it open while we’d been in the Walgreen’s? I opened it and Tracy’s roll-on suitcase tumbled out into my arms, which is what I guess it would have done on the road the first time I accelerated sharply. Nothing was missing, though the mystery of how the trunk had come open remained. We decided we were too paranoid to risk it and piled everything on the back seat before buttoning up the top one last time. As we drove, I tried to keep track of the billboards that involved plays on laissez le bon temps roulez (e.g., “laissez le profits roll”) but lost track after about six or seven.

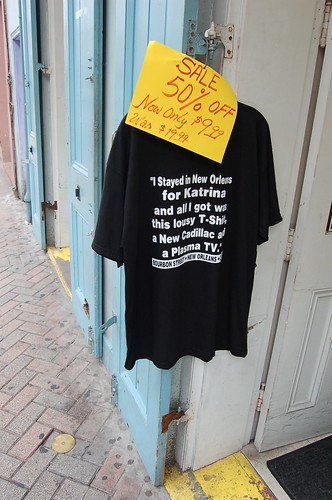

In the French Quarter, we parked in a valet garage in hopes that this would keep the luggage safer (adding nine more dollars to the tab for our “cheap” method of getting to New Orleans, but of course a cab ride to the airport wouldn’t have allowed us to stop for lunch in the FQ) and set out on foot. A sidewalk hawker in a plaid shirt and striped tie tempted us into The Alpine, “a Louisiana Cajun Bistro” that turned out to be owned by the same people who run Oceana, the delicious seafood restaurant where our group hat eaten on Thursday night. During lunch, I noticed a headline on the TV: “Police shoot 80-pound lizard – unclear if it’s dead or just wounded.” Our po boys were delicious. We asked them to pour the last of our beers into “go cups” and set out to stroll the quarter. I wanted to at least look at Preservation Hall, a historic jazz venue that my dad, the jazz writer, had urged me to check out. (I see now, having just gone hunting for a link you could follow to learn a little more about the place, that I didn’t find the right one. I found someplace called “Maison Bourbon – Dedicated to the Preservation of Jazz” and assumed that perhaps the name Preservation Hall Jazz Band had simply adapted part of the name of the establishment. But I can see in the Wikipedia article’s photo and in the real Preservation Hall’s virtual tour that the building looks different from the place I found. Oh, well, pays to do your research ahead of time, I guess.)

We walked the narrow streets and took in the sights, the neighborhood seeming to blink in the bright sun. The sights included beautiful, time-ravaged old buildings, a splash of vomit by a bench, a “statue guy” performer posing as a football player in mid-pass, and strippers arriving at a club for an early shift. When we couldn’t take the oppressive heat and still, fetid air any longer, we struck out for Jackson Square Park, which turned out to be less shady than I expected. There was a guy selling prints by fence on the Riverwalk side of the park. At first the primitive, blocky designs looked appealing, but, when he started showing us how many different sizes and colors he had of each print, it all started to feel a little too mass-produced to be worth $30-$40 a print. We moved on after he asked me if I were studying creative writing “to impress my girlfriend.” “That’s not my girlfriend.” “But you’re still studying creative writing to impress a woman, right?”

What?

It was getting late and we had neglected to mark the precise location of our parking garage, so we picked our way back from one landmark to the next. A bar called Frat House. Hustler Hollywood, “home of the Hustler Honeys,” in case you’re ever looking for them. A balcony with a large papier mache head suspended from ropes. Jean Lafitte’s Old Absinthe House, which does not serve absinthe.

Back at the garage, Tracy went in search of a bathroom while I ordered up the car. As I waited for a valet to drive it down, his honks at blind turns echoing down through the levels of the garage as he got closer, a woman with an expensive-looking hairdo and wearing a black suit sat on a bench waiting for her own car, smoking a skinny cigarette. Another garage attendant, a heavy black woman in a sweat-soaked red polo shirt emblazoned with the name of the garage, asked the woman how it was going. Her tone did not give me the impression that she cared to hear much of an answer, but the blonde was off and running. “Well, I just got back from a business trip and they took us to a golf tournament and I didn’t know how to behave, I mean I guess you got to be real quiet and stop walking when they’re putting, I don’t know but I was about to get myself booted out of there.” The attendant nodded slowly, staring into space and fanning herself weakly with her hand. I had the distinct impression that, while the attendant might not have known how to behave at a golf tournament either, common ground had not exactly been established.

On the way out of town, next to the I-10 on-ramp, a giant billboard tempted drivers to a casino where they might win “one out of fifteen John Deere tractors.” In only slightly smaller print at the bottom of the billboard was the required advisory as to where to call if you have a gambling problem and want help stopping. In heavy westbound traffic, we found ourselves stuck behind a truck with a hand-lettered sign on the back: “Ladies go topless.” But in case you might be tempted to take offense, the driver had drawn a smiley face on the sign, too, so you would know it’s just good clean fun. We stopped at the edge of the airport for gas ($13, bringing our “cheap” ride to a grand total of a little over $100) and then had a hell of a time finding the Thrifty drop-off, which was not mentioned on any of the airports’ rental-car return signs. But we had allowed plenty of time, as it turned out, and arrived at the airport with a good hour and a half to go before our flight. I had trouble in security because I’d forgotten to remove the two bottles of water I’d taken along from the hotel room that morning, plus they also said I looked cold, calculating and dangerous, but I get that all the time. I talked my way through before too long. On the way to our concourse, Tracy asked if I had noticed the man ahead of us, traveling with two boys, who had carried his “go cup” of beer right up to the verge of the metal detector before downing it in one long chug. It was a shame about my water bottles, as I’d been dying for some water since leaving the French Quarter and hadn’t realized I’d had some all the time. I bought another one in the concourse for $4. I had to ask the clerk to repeat the price when she said it. I haven’t gotten that ripped off in a long time, but what are you going to do?

The walk in the quarter had exhausted me and left me grimy and sticky. I would have given anything for one last afternoon nap in a soft hotel bed but had to settle for sinking into a bench seat in the gate area. These seats looked soft but weren’t and only supported me up to about my middle back, as if they had been designed to discourage you from sitting in them for too long, which just seemed cruel under the circumstances.

My flights home were largely unremarkable, but I offer the following two findings for the sake of the permanent record:

1. Either I had the same pilot as when I’d departed Baltimore, or AirTran pilots in general really do favor especially sharp ascents from takeoff and long, dramatically pitched banking turns above the airport. Exciting!

2. Leaving your cell phone on during flight does not cause the plane to crash. I discovered this the way all true scientific research is done, by hazarding myself (and my fellow passengers) in mad pursuit of knowledge. Actually, I was just reluctant to turn the thing off because it does not reliably turn back on again, in which case I was afraid I might not be able to find my brother at the airport in Baltimore. I was reasonably confident that I would survive this experiment for two reasons.

a. The pilot, in his announcement concerning such devices, said “discontinue using” them, as opposed to “turn them off,” and I figured he would have more precise knowledge of the nature of any potential problems than would the flight attendants, who favored the “turn them off” formulation.

b. If cell phone signals actually posed a hazard for the plane, why on earth would we be allowed to bring them on board? You’re telling me I can’t bring a five-ounce bottle of mouthwash but I can carry a deadly communication device that will send the plane screaming toward the ground at the touch of a button? As we were circling Baltimore, I almost chickened out and turned the thing off, though, when it occurred to me that maybe I shouldn’t be gambling my life based on policies set by the federal decision-makers responsible for the nation’s safety and security, who do not generally seem to be what you would call “sensible” or “good at their jobs.” But I held out and before long we were safely on the ground.

At the baggage carousel, my suitcase popped open when I grabbed it from the conveyor belt. The AirTran packing tape I’d wrapped around it was broken, I noticed. I later found out that this was courtesy of TSA, who’d left one of their random inspection calling cards behind. I also found out later that the gift jar of “crawfish jelly” I’d packed inside was broken, although fortunately I had put it in a Ziploc and hardly any of it had leaked out. I want to blame TSA for this, though I can’t be sure it was their fault. I guess I just will blame them anyway.

Stupid TSA.

We piled my belongings into my brother’s Ford Taurus and made our way home, seeming to hit every red light possible on the way. After my restless sleep the night before, the 1,000-degree hike through the French Quarter, and a layover in Georgia, I was barely conscious by the time I crawled into bed, leaving my unpacking for Tuesday.

It wasn’t as soft and fluffy as the bed in the Sheraton, by the way.

Sunday

The morning after the wedding found me standing on the levee while the groom hunted for his bride in the underbrush along the Mississippi.

That was a fun sentence to write but I may be giving you the wrong idea. We had all simply gone for a stroll, and Erin had diverted from the pack to take a look at a pile of river-polished glass she knew of. But the heat was getting oppressive and we all wanted to head back to the hotel, so Greg jogged off to find her and tell her what we were doing.

To start from the beginning, A. and I had dawdled in the room until almost ten before heading downstairs for the breakfast buffet. On Saturday the buffet had closed at ten thirty and we figured we had at least that long on a Sunday morning. We were in the lobby by 10:10 a.m. but this was too late, because, for some reason, the buffet closes earlier on Sundays than on any other day. We waited around for twenty minutes until the main restaurant opened and had breakfast there, instead.

After breakfast, the newly hitched couple invited us along for a walk out on what Erin calls “the rusty old dock where you can see everything.” This turned out to be a disused cargo pier about a half-mile down the levee from the hotel. A rusty metal truckway led out to a massive concrete platform, with the I-10 bridge across the Mississippi towering nearby. Actually walking out along this rusty metal seemed like a terrible idea to me, but it was one of those terrible ideas that groups of people tend for some reason to be ill-equipped to reject. One lone naysayer goes along anyway, muttering things like “this doesn’t seem safe,” sure that he’ll be the first to fall through once everyone else has weakened the metal.

But there were no fatalities and the view was grand, more tugboats tugging past, a river of traffic pouring across the river on the bridge, hobos’ fishing poles bobbing in the grasses along the bank. In the water, at the base of the pier’s pilings, a massive raft of driftwood (by which I mean tree trunks) bobbed in a smear of bright green silt, along with dozens of Dasani water bottles. So healthy and natural to drink water, but then where do the bottles go? Where do they come from, for that matter? Nowhere healthy and natural, I’ll wager.

After the bride and groom found each other, we all walked back to the hotel to shower and change for the afternoon’s eating, a crawfish boil at Erin’s parents’ house, Erin’s parents who do not ever stop. I’d never eaten crawfish this way before – hardly any way, actually – and it was a treat. The basic set up was like a crab feast, for those of you who know those: seasoned, boiled crustaceans are poured in a pile on a table, and you crack them open and pick out the meat. Crawfish are delicate enough that no mallets or crackers are needed, however, and it is pretty fast going to suck down a good amount of the lobster-like flesh. The seasoning involved red pepper (“don’t rub your eyes,” called out the cook for the benefit of the newbies) and something that smelled like holiday mulling spices. The crawfish that hadn’t been cooked yet awaited their doom in netted sacks like laundry bags before being poured out in a bucket for washing and salting. Then into the boiling water with seasonings, potatoes and corn-on-the-cob in a pot the size of a cut-off 50-gallon barrel, over a propane flame that roared like a jet engine. The men took care of the preparations and cooking. Down in these parts there is a strong tendency toward traditional gender divisions of labor, but any kind of cooking that involves heavy equipment and the possibility of explosions is gladly taken on by the men. (And I shouldn’t perpetuate the stereotype: Erin’s dad had cooked the jamabalaya for the wedding and also makes a mean praline, the recipe for which was a deathbed bequest from an old friend of his on the condition that he would never ever tell. And he won’t.) The crawfish was served on an aluminum table custom built for the purpose, about bellybutton high on me with a hole in the middle for a trash chute. One young woman had brought her parrot, which perched on her shoulder and nibbled cheese from her fingers. It made an occasional lunge for some crawfish but she would swat it away.

After the crawfish, people revisited the food they’d loved best the night before. The microwave beeped and whirred as guests reheated jambalaya; there was more potato salad; pralines were brought out on a platter; and alliances were formed for the purpose of eating more cake (“I’ll get a plate with a couple of different kinds and we’ll share”). The conversation turned to the weather and the locals all agreed that we’d been blessed with unusually cool temperatures this weekend. “Usually it’s already oppressive this time of year, and we’ve been getting a lot more rain than usual.” I found myself thinking that no one seems to know what to make of the Baltimore weather either; it can’t quite seem to settle into the expected balminess of late spring in that area. Have we reached some sort of tipping point? Are people all over the country having these kinds of conversations? “We never used to have so many locusts, neither…”

To walk off the food, Erin and her brother led a walk down to the edge of the subdivision and along the bayou, through dense underbrush that at least one guest can attest included poison ivy. The air was still and hot among the trees and two young girls who had tagged along seemed to regret their decision to join us. We finally fought our way back out onto the power-line right-of-way that runs behind Erin’s parents’ house but high grasses kept us from making a straight shot. A local homeowner was upset at our decision to crush down a wire fence for the children to hop over. “Just step on the ‘No Trespassing’ sign,” said one little boy just as a woman walked up in gardening togs and a sour expression. “The fence is there for a reason, you know.” We were sorry but not sorry enough to turn back. Erin’s brother and two others straightened the fence back up the best they could as the woman walked off in a huff. Guess her life hasn’t turned out the way she hoped. Nice garden, though, but that just kind of proves my point.

We passed the long slow hours of the late afternoon and early evening talking in the shade of the tent that had been erected for the wedding. Erin’s brother told us about his tournament bass fishing avocation, and the sideline business he has making custom bass “buzzy bait” lures. Various guests tried their hands at creating frozen drinks with a newly purchased blender (purchased because Erin had had an itch for daiquiris and had taken everyone’s order before she remembered that “the drive-through daiquiri stand isn’t open on Sundays”), and with each attempt the vodka or rum content seemed to rise. It really was only a coincidence, though, when one guest tipped over backwards in her chair and took a whole folding table with her. When I walked inside to use the bathroom, I found the Tennessee cousins sprawled on the couch, ceiling fans humming overhead. The men were watching auto racing (not sure if it was the Indy 500 or the Coca Cola 600) while the women dozed.

After a certain point, I could no longer ignore the dreadful fact that this was the last night of the trip; on Monday, A. would leave bright and early for Arizona and I would catch a later flight to Baltimore and we wouldn’t see each other for another few weeks at least. So we jumped at the chance to catch a ride home from a sociology grad student, a friend of Erin’s, and we were back at the hotel before nine. We watched a few Office episodes that I had brought down on the laptop and received a good-bye visit from Erin and Greg when they got back to the hotel around midnight – after being forced to open every single wedding present for an audience of friends and family, so thank god we escaped when we did. At around one a.m. we set the alarm for six and tried to get some sleep. Can’t speak for A., but it wasn’t the most restful night for me as I (1) regretted we’d be parting ways the next morning, (2) worried that the alarm might not go off, and (3) tried to hurry up and go to sleep before too many more minutes ticked by on the big red digital display, which, if you don’t know, is not a good technique for trying to fall asleep.

The Big Easy Wedding, pt. 4

Awakened by loud knocks at nine a.m. You rent rooms in these places and everyone just wants to come in. We told the maid to come back later and hung out the “Do Not Disturb” sign for a little more sleep but the spell was broken so we headed downstairs for breakfast. The Sheraton offers a breakfast buffet in its sun-drenched glass-ceilinged atrium, $11.95 and all you can eat. Which never turns out to be much. These people know what they are doing. We ran into Erin and Greg and sat together at a table under some potted palms. Omelettes were available from a courtly chef in a tall hat and we sipped coffee and nibbled at fresh fruit while we waited for him to fry ours up. All in all it was a great buffet, but, in what would turn out to be a pattern for the weekend, the waiters and other staff never quite seemed to be ready for prime time. There was, for example, the difficulty of getting our coffees refreshed. Why was everything self-serve except the one item people are physically addicted to? Restaurant meals just jump the rails for me when I run out of the accompanying beverage. I sit and stare at the food growing cold on my plate, not wanting to keep eating because I know I’ll enjoy it so much more when I get a fresh drink. Next time I’m in a situation like that, I’ll order two cups from the start. We weren’t the only ones who had trouble. Aaron and Julia waited ten minutes after loading their plates for someone to arrive with silverware. Alison’s coffee never arrived, so, as she and Kevin were finishing up, she repeated her request and asked for it to come in a to-go cup. The cup arrived, but it was empty. Later, I had occasion to call guest services for help researching how I would get to the New Orleans airport on Monday. Every question I asked met with the same response: “I’ll look into that and call you right back.” I wasn’t asking how many hot-water heaters the hotel had in the basement; you’d think that, in a “full service” Baton Rouge hotel, the answer to the question “how can I get to New Orleans” would reside in the reference binder next to the guest services operator’s phone.

But I suspect that there was no reference binder at all.

All petty complaints aside, we quickly became addicted to life inside the Sheraton’s shell. I’d never stayed in a “full service” hotel before, but I quickly saw the appeal, especially for this type of travel where one is not from the area and is also not really visiting “the area” (scenic downtown Baton Rouge, anyone?). Anytime we went anywhere we were dependent on other people for a ride, and dependent on their schedules as well, but we were in control inside the cocoon of the hotel.

The wedding ceremony would start at seven p.m. so we guests had the day off and a large party of us retired to the pool. There were pitchers of pina coladas, rum-soaked cherries, and synchronized swimming. Aaron stood on Kevin’s shoulders and left him bruised. I got some typing in but soon had to abandon the effort in favor of socializing like a human being. Such strange customs your species has…

For lunch, the groom wanted to go to Frostop’s, a local greasy-spoon chain. Kevin and Alison went along but A., Natalia and I decided we wanted to lay in some sort of counterbalance against the caloric excess of the upcoming reception dinner. We retired to Shuck’s on the Levee, one of the hotel’s restaurants, with a window-seat view of the casino boat and the muddy Mississippi, the tug boats chugging past with immense strings of barges. We ordered salads and were glad to finally finish a meal without feeling painfully full before even swallowing the last bite. In the late afternoon, everyone met up at the bar for a last round of drinks with Greg as a bachelor, as meaningless a term as that is among people who tend to live together for years before “the question” comes up, and then we all headed to our rooms to gussy ourselves up for the big night.

The wedding was an outdoor ceremony behind Erin’s parents’ house, officiated by a Unitarian minister who for some reason worked the fact that he was a Unitarian minister into his service about a half dozen times. Two to three hundred people watched from white folding chairs ranged in the grass. Trees loomed overhead (and power lines), and birds provided musical accompaniment. With the ceremony over, guests helped themselves to homemade etouffe and artichoke dip and crackers and cheese for appetizers, with two massive vats of jambalaya for the main course. One of Erin’s cousins, a mortician who moonlights as a limo driver, tended bar and mixed them strong. A local band played for the dancers, the average age of whom was kept low by a pack of little girls who spent the evening whirling and running across the dance floor. The cake cutting was in the living room, where a table groaned under the weight of nine different cakes. A groom’s cake in the next room was fashioned to look like a cheeseburger the size of a car’s tire.

The wedding party’s tuxedo rentals had been of sufficient quantity that the store had thrown in a limousine ride for free, and Erin and Greg were nice enough to offer a ride for everyone headed back to the hotel. Sometimes you see a limo going by and imagine that a wild party is ensuing behind those tinted windows, but really it was all we could do to stay awake.

The Big Easy Wedding, pt. 3

On our second morning at the Dauphine Orleans, we bestirred ourselves in time to go down to the breakfast lounge together. A. made waffles while I hovered over and then secured an outside table by the pool, as soon as it was abandoned by a European-looking man chain-smoking cigarettes with very long, white filters. I moved his ashtray and trash to one of the small tables by the chaise lounges and then proceeded to make approximately five dozen trips back in and out of the lounge. Hardboiled eggs? Yes, I’ll take some of those. Oh, and how about some mini-croissants. Slices of cantaloupe. Oops, forgot napkins. And forks. As I banged in and out of the door, I heard snatches of the phone calls being made by a man in the corner, his laptop open on the table in front of him. He’d been there Thursday morning as well, loudly barking something like “well, I won’t have it in front of me at the conference call, so you should just be like, ‘Dave, remember, you said da da da da da.'” His cell phone seemed to be set to make the loudest possible beeps when the keys were pressed, as if he wanted to make sure that everyone noticed when he did so. “Can everyone tell that I’m dialing my phone?”

It was a beautiful, clear morning and I did finally feel as if I had gotten caught up on sleep, even if I had been awakened briefly around four a.m. by what sounded like dumpsters being emptied and then repeatedly slammed against the truck to get every last scrap out, in the street below our window. I wrote up the diary before check-out and then we met Erin and Greg and their Austrian friend Felix (currently based in Bucharest but working in Istanbul) in the garage, crammed everyone’s luggage into a white Buick that turned out to be missing essential components of its suspension system, and set out for Baton Rouge.

Traveling through New Orleans in the daylight, I was alert for signs of destruction, remnants of the storm. I couldn’t convince myself that I saw any, but the town definitely has an off-kilter feel to it, weirdly empty in some blocks and then suddenly choked with traffic around the corner. At a stoplight, the driver of a mini-van kept staring at us. Or maybe he was just lost in thought, not really looking at us at all, but I began to think about the menace of the south. Such a higher concentration of people down here who know how to shoot and gut things and may even have the necessary tools close to hand. I kept my eyes straight ahead until he pulled away from us after the light turned green.

The first half of the drive was along the long, straight raised causeway that skirts the swamps and the edge of Lake Ponchartrain. The first glimpses of the lake were of small inlets interrupted by heavily wooded areas, more of a maze than a lake and not really all that impressive as bodies of water go. Then we got out along the edge of the lake proper. It looked muddy and the wind was whipping up small whitecaps; huge pylons carried power cables through the middle of the water, which now looked plenty wide enough and deep enough and potentially angry enough that you definitely wouldn’t want it draining at speed into your neighborhood.

Past the lake, the terrain turned into the standard suburban sprawl you find near any American city. The only obvious signs we weren’t in Maryland were the palm trees and the armadillo roadkills. Religious country, but what isn’t these days: massive white crosses of the trinity loomed over a Hummer dealership; a contractor’s trailer we passed on the highway displayed crosses as well, worked into the logo painted on its side. As for the wages of sin, a massive billboard advertised for candidates to become correctional officers. The main selling point, in large, eyecatching lettering: “$1,530 per month, plus benefits.” We passed a massive water park at the cloverleaf exit for Erin’s parents’ house. The Hooters where Greg once worked as a cook. The house was far removed from this kind of detritus, though, and sat back in a quiet cul-de-sac, massive old trees looming overhead and a backyard that stretched for perhaps a quarter mile before hitting woods. Erin promises to show us the bayou back there on Sunday, at the post-wedding crawfish boil. Tiki torches lined the front walk. There was a smell of many different kinds of food cooking and the kitchen was supplied as if for a siege. A small girl was introduced as a flower girl and hid her face at the terror of meeting new grown-ups. (Wait, is that what we are?) Back in the car and off to the hotel. The bride and groom had things to do.

The Baton Rouge Sheraton contains a convention center and a casino, just to give you a sense of the place’s scale. The glass-roofed atrium lobby looked large enough to hold some cathedrals I’ve seen, with plenty of room for bars, restaurants, seating areas. The only thing missing was some sort of fenced-off canopy at the top, up by the roof, full of rain forest plants and monkeys, or maybe sloths would be more practical, less disruptive. It would be nice to sit with a drink as the sun sets, listening to the plaintive songs of the sloths, if only sloths would in fact sing. Maybe they would if they could live in a Sheraton. You know, out of gratitude for the essential decency of the human race. But no such luck. The potential is wasted.

A bellhop took us to our 10th-floor room. We needed to use our room key card in a slot in the elevator in order to be able to select our floor, up on the “club level.” View of the Mississippi, over the top of the U.S.S. Kidd Museum. We changed and headed down to the pool, first stopping by the front desk for the yellow armbands necessary to prove our right of access to the pool. We also stopped by a bar, where they poured our frozen drinks and then poured us each a second glass, saying “here’s the rest of the drink.”

Out on the pool deck, the armband thing seemed to give the other guests trouble. No-nonsense guards passed by frequently and challenged anyone who wasn’t making the right display. The guests and the guards seemed equally frustrated, and, in defense of the guards, there is a sign explaining about the armbands on the door to the pool deck. But an old man sunbathing with his shoes on was chased back up to his room when he could only produce his room key (meaningless; apparently, anyone might have one of those, but no one except registered guests could possibly get one of these little plastic armbands), shaking his head in disbelief. It is strange to charge people these kinds of prices and then hassle them when they are trying to relax by the pool. Seems like an example of a company passing its problems on to its customers. There may in fact be a problem of trespassing at a place like this, but it’s not our problem. Figure out how to make it work, don’t bother us, and can you bring us another round of daiquiris on your way back out? That’s how it should work, seems to me, but I wouldn’t be the first to note that the world can sometimes be an unjust place. Nothing to do but soldier on, keep to the code, non illegitime carborundum.

In the evening we piled into Kevin’s car for the drive to the rehearsal dinner. We picked up Felix at his hotel and were hardly late at all, though this is a distinction without much meaning for Germans, an obsessively punctual people. At the party, there was gumbo and potato salad and people playing with fire out in the wide, flat backyard, under the power lines. The evening was cool and pleasant and there were no bugs, due to a specially-ordered custom pesticide application. (Otherwise, the city takes care of it, sending poison-spraying trucks through on a regular schedule.) A mimosa tree was in bloom with blossoms like pink cotton candy. The blackberries were ripe in the garden patch, where a tomato plant loomed over everything, fully seven feet tall and three feet around. In late May, mind you.

As the darkness deepened and the burners put away their flaming hula hoops, I drifted into the kitchen for more gumbo. The cook, a friend of Erin’s parents, seemed to have been perfecting his art as a sort of life’s work. “I love cooking gumbo. There’s about fourteen of us get together, every month or so, and I’m always trying to make it better. I didn’t make it real spicy, so the out-of-towners could season it how they want. I don’t like boiling the meat off the chicken. Some people do that, but I use a deboning knife.” I asked him if that’s hard. “Well, it takes a lot of practice.” I dashed some Louisiana hot sauce on my second bowl and the cook’s eyes widened. “Whoa! You like it hot, huh?” I told him I did, although I wondered if I had erred and would soon have sweat streaming down my face. But the sauce was about as hot as the tabasco sauce it resembled and the gumbo was heaven in a paper bowl, one spoonful at a time.

The fire show that had taken place earlier had been put on by a friend of Greg’s and the friend’s wife. She had danced in flaming hula hoops, while he had “blown fire,” gulping in big mouthfuls of paraffin oil and blowing out across a flaming torch. Her act involved the real skill; his had the feeling of a parlor trick that anyone could learn and wasn’t all that impressive after the first few times. A. and I found ourselves talking to him and he was full of advice. “You have to get a good mixture of air in the fuel.” (Maybe to keep the fire from running backwards to your mouth? Not sure if that was his point.) “Try it with water first. When you get the point where can blow out a big cloud, instead of a stream, you’re ready.” At least they paid attention to safety. One audience member had been assigned to sit close with a fire blanket, and an ABC fire extinguisher stood close to hand. But it was hard to take the safety talk seriously when the fire-blower still wore a beard, which just seemed like kindling under the circumstances.

Back at the Sheraton, we decided to check out the casino. We followed the arrow on the huge sign in the lobby, expecting that the casino would be in the next room, but instead found ourselves walking through long passageways and riding up and down escalators as we followed the well-marked route to what we later realized was a casino boat, though there was at no point any sign that we had entered a boat and never any sensation of movement. I figured that it was only technically a boat, i.e., a building that wasn’t actually attached to the ground at the bottom of the river, but the next day, from the window of the hotel restaurant, I could see a mast and a radar antenna. We passed through a security checkpoint, where we had to show ID before entering. The guard stared at Felix’s passport for a long time before looking him in the eyes and solemnly intoning, “certified!”

It’s an awkward feeling, walking into a casino when you have no intention of gambling. Greg, Kevin and Felix wanted to play a little blackjack, but A. – though she knows the game, courtesy of an uncle who is something of an expert in these matters – said she didn’t feel confident enough to play at an actual casino table, and I figured that – if I discovered any money that I didn’t want – it would be faster and easier to just set it on fire. So we were like the people who keep their clothes on at an orgy. “Oh, none for me thanks, just watching.” I must say it was not the most uplifting spectacle. Most of the boat’s four levels were given over to slot machines, which must be the most solitary and alienating form of gambling, with not even the pretence of social interaction you get at a card game. The gaudy lights on the slot machines lit everyone’s faces with a neon glow, like daylight times two. I could see how, if you wanted to gamble, this kind of decor would keep your energy up and might even look good when you first walked in. The smoke of a thousand cigarettes hovered in the air. Video monitors showed fictional images of people winning, young attractive couples pumping their fists in the air, a smiling white-haired woman just glad to be able to afford more ribbon candy for her grandchildren. Such scenes did not seem to be playing out on the floor of the casino, however. I don’t remember even noticing anyone smiling. On the way in, there had been a “winners’ wall,” photographs of the actual victorious, identified only by first name and last initial. Purses ranged from $4,000 to $1,317,204, although my eye was caught by the oddly precise $745,131.84 won by one Debra O., with something about her eyes that suggested that this payout had been a long time coming.

We left the boys to their blackjack and headed out in search of a last drink; the casino wouldn’t serve you unless you were sitting at a game. But no one else wanted our money, it seemed. It was only just midnight, but the hotel’s restaurants and bars were all closing up for the night, palisades of upside-down chairs and stools fencing off the seating areas as mop crews set to work. “You could get a drink in the casino,” said a guard, in what sounded like a practiced line. No thanks, and off to bed.

Possible epigraph for the evening: “Tell me something you’re really good at. Besides bullshitting.”

The Big Easy Wedding, pt. 2

The sun streamed in through the louvred shutters and it was a good feeling to be waking up in New Orleans. I left A. in bed and walked down the stairs to the “breakfast lounge,” a sunny room next to the pool. The offerings included make-your-own Belgian waffles and some fresh fruit, but none of the local delicacies I’d hoped for. Not bad, though, as these “continental” breakfasts go. I toasted two bagles and loaded a plate with cantaloupe slices, hardboiled eggs, and two donuts, and poured one cup of orange juice (all I could carry, figured we’d share). Back at the room, A. made coffee and we retired to the balcony to eat.

It was late, and then there was yesterday’s entry to type up, so we didn’t leave the hotel until after noon. We briefly tried to orient ourselves to the French Quarter via web sites but it was too confusing, too many bells and whistles, so we put on sunglasses and headed out through the lobby, grabbing a simple paper map on the way.

We had exactly one official goal, picking up a copy of the classic comic New Orleans novel, Confederacy of Dunces, for A. Again, we had tried to locate nearby book stores on line, but the search hadn’t told us that there was one across the street. We pushed open a sun-worn wooden door and found ourselves in the standard used book store, tall ceiling, dark, aisles almost impassable with teetering stacks of books, no immediately obvious system of organization. A cat flitted by. No Confederacy of Dunces. “I sell those as soon as I get them,” said the owner. We left and walked to the book store we had located on line, Arcadian Books and Art Prints on Orleans Avenue. Arcadian had a new copy of a recent edition, his last one. “I can’t keep them on the shelf,” said this owner.

Our errand complete, we strolled the quarter. The program for the day was that a large group of friends would meet the bride and groom around seven p.m. for a night out in the French Quarter, but, until then, we had time to kill and just felt like exploring. At this hour – in the early afternoon – the neighborhood had a bleary, empty feel; I had the sense that preparations were being made. It was difficult to get used to the sight of people drinking in the street. There weren’t many, yet, but a few hardcore types clutched plastic cups and even bottles, which I’d understood was a step too far. The police didn’t seem to mind, though. The businesses have naturally adapted to serve a clientele interested in drinking in the street. One t-shirt shop had a small counter at the edge of its open entryway specifically for selling takeout beer. Another shop displayed a large sign: “Big Ass Cups of Beer To Go.” But drinking in the street was only one of many options. Some of the bars were already filling up, the remnants of the lunch crowd mixing with those getting an early start. In one mostly empty establishment, strange octopus-like contraptions dangled from the ceiling along the bar. They looked to us like multi-person beer bongs, or devices with which a beer can be delivered to your gullet through a tube with the force of gravity behind it. Usually this is a simple tube used by one person at a time; one person pours in the beer while the drinker holds the tube up to his mouth. This sort of appliance is assumed to be a standard feature of the college years, although the only place I ever ran into one was in an apartment I was sharing with two other Coasties in Miami in the 1990s, when, at a housewarming party we threw, I was startled to see that some of the guests had adapted a garden hose to this purpose and were standing in a flowerbed, drinking beers that someone else was pouring in from our third-story balcony. About the same time that I realized that these particular guests were underage (so it goes, when a military unit is hanging out together), the cop who lived in the complex was just getting into his car and leaving for work. As he drove by, he actually put his hand up to the side of his face as if to block his view of this spectacle, perhaps wanting to actually clock in for his shift before he had to start processing an arrest. I took the garden hose from the balcony crew and hid it in a back bathroom.

Speaking of balconies, in our exploration of the French Quarter, A. and I turned a corner and happened upon an impressive method of loading cases of beer into the second story of a restaurant. One man stood next to a Bud Light truck, pulling cases out of the truck and then heaving them up to a man standing on the top of the truck, who then tossed them to a man standing on the balcony. The hardest job of the three was the first, since he had to heave full cases of beer about six feet above his head. He looked like the new guy, his arms not quite as ropy and hard-looking as those of the other two men, so – even though less able to do the job – he’d been given the grunt work. As we watched, he seemed to visibly tire, and his last couple of throws barely reached the top of the truck even though he had put his flailing all into them. “Now that’s how you deliver some Bud Light,” said a passerby.

We didn’t get much further before we realized that we were hungry for lunch and stopped at the Turtle Bay Cafe Roma for sandwiches. They had just gotten a 15-pizza delivery order, they warned us, so our meal would take a little while. We didn’t mind and enjoyed sipping our beers in the cool, dark bar, watching the people streaming past on the bright sidewalk outside.

In the late afternoon, we strolled back to the hotel. A couple of beers, our full bellies, and the warm sun – not to mention our late arrival the night before – had left us drowsy, and we wanted to get a quick nap in before what we expected to be a demanding evening. We hung a “Do Not Disturb” sign on the door, closed up the blinds, and climbed into bed. I was just dropping off to sleep when the phone rang, loud, jangly and piercing. A. answered. In my half-awake state I couldn’t follow exactly what was going on; I thought that perhaps one of our friends was trying to reach us to let us know where to meet up for the evening. (I’d had the foresight to turn my cell phone off before the nap, so they wouldn’t have been able to reach us that way.) But when she hung up, she explained that the front desk had called because “an engineer needs to get into our room to do something to the tub.”

“But he’s going to check and see if the engineer has to get in right now or if he can come back later,” A. said.

I took the return call. Sorry, said the front desk, but the engineer needs to get in now. I felt myself turning incandescent with rage. The last good night’s sleep I can remember getting was in 10th grade, and I don’t think I’ve successfully fallen asleep for a restful afternoon nap since I was about seven. Sometimes I think I will never feel fully rested again for the rest of my life, so it had been with no little surprise and pleasure that I had felt myself dropping off to sleep.

“This is a funny way to run a hotel,” I said. “I paid for a room and I was using it to take a nap. I didn’t want to be disturbed, which is why there was a “Do Not Disturb” sign on the door.”

“Oh, yes, I know, sir,” said the clerk. “That’s why we’re calling. Because of the sign, we didn’t want to risk barging in on you.”

I was too befuddled with sleep to grapple with what I later realized was the insanity inherent in this statement, hinging as it does on a rather unconventional understanding of the concept of not disturbing someone. I hung up on the clerk, hunted up some clothes, and opened the door for the engineer. A. and I retreated to the balcony while he worked. I was so angry that I was shaking and there was a moment or two when I was afraid I might actually throw up my lunch, which was suddenly sitting on my stomach like a brick. For this I was paying $100 a night? To be treated like they were doing me a favor by letting me stay in their hotel? To rent a room and have it to myself – unless of course someone needs to come in? A door slammed. I wondered if the engineer was done but assumed that, since he had noticed how angry I was when I let him in, he would have been at pains to let me know that he was leaving so that I could get on with my afternoon. But after a few more minutes with no further sign of him, I climbed back into the room (balcony access is through a large window, for some reason), slamming my head into the window sash in the process.

Sleep was out of the question, I realized as I sat on the edge of the bed, rubbing my head. I picked up my socks.

“I’m going to go talk to them,” I told A. “I’m not paying for today.”

I grabbed the “Do Not Disturb” sign off of the door and walked down the stairs to the lobby, trying to get my thoughts in order so that I would not lose my temper or swear. The clerk was apologetic, though, and this defused the situation, plus he had what sounded like a good excuse, until I thought about it some more later.

“I thought the engineer needed to get in to fix a problem that you had called about, sir,” he said. “That’s why I called. I sincerely thought I was expediting something you wanted taken care of. I didn’t realize that the engineer just needed to get in for a routine check.”

He kept apologizing, but the desired “and we’ll give you a free night” never came, and I could never bring myself to ask. Eventually, shamed at my lack of a spine, I slunk away, thinking that maybe I would just dispute the charge later with American Express. As I once again lay in bed, knowing that I would never be able to fall asleep but hoping that if I just closed my eyes for a little while the choking sensation of rage in my chest might dissipate, I realized that the clerk had been lying. If he had really thought that the engineer was responding to our service request, what had he made of A.’s confusion when he called the first time, and my anger the second time? What would our reaction have needed to be to indicate that we were not, in fact, awaiting a service visit? Maybe he would have gotten the message if we had blown a police whistle into the phone. Actually, I’ll never again go to sleep in a hotel without unplugging the phone first.

Then I started to dwell on the little piece of information that the clerk had let slip. The engineer had only needed to get in for “routine maintenance”? For no particularly urgent reason, in other words.

And seeing a “Do Not Disturb” sign on our door, what did he do?

He called down to the front desk to request that they, um, disturb us with a phone call so that he wouldn’t have to do it by knocking.

I realized that the clerk and the engineer would both have to die.

I reached under the mattress, retrieved my pistol, and racked a round into the chamber. A. immediately started packing and wiping the room for prints.

Not really (that’s the Cormac McCarthy novel’s influence talking), but goddamn, what a way to kick off a weekend in New Orleans. That’s the Dauphine Orleans Hotel, people. Do me a favor and stay away, and tell them I didn’t send you. (And what a shame, because otherwise it seems like a great place. If they make it up to me, I’ll let you know that you’re allowed to stay there again, but if they don’t, and you do stay there, I’ll bury you right next to the clerk.)

A. managed to fall asleep again and I booted up the laptop and wrote up the story of the “Do Not Disturb” sign. Then I got out my diary and noted that I had written in my diary. Then I wrote in my diary about writing about writing in my diary in my diary.

Telephone calls were made. Text messages were sent. The plan came into shape. A. and I showered and dressed and left the hotel around 7:30 to walk over to Kevin’s hotel, where the bar, Ohm, had been tentatively selected as the evening’s stepping-off point. At first I took “ohm” to be a reference to the Hindu peace mantra they make you chant after yoga classes, but the sign also included the upside-down horseshoe symbol for the metric unit of electrical impedance/resistance (also known as the “ohm”). Meanwhile, the decor was Asian, with rice-paper style watercolors of Samurai and ceramic imitation takeout buckets for candleholders. Lava lamps and psychedelic projections and mechanical-sounding drum-heavy music added a further layer of ambiguity as to cultural referents. Kevin convinced me to order a Blue Moon, a Belgian white ale whose appeal was not apparent to me. It came with an orange slice, like they used to give us at soccer games when I was eight. The discussion turned to french fries. McDonald’s makes the best, everyone agrees, but there is such a small window of time in which they are edible. Wait to eat them for even a quick car ride home from the restaurant and they will be soggy memorials to what might have been by the time you unfold the bag. Such, such were the disappointments when I was a child.

We met the bride and groom at Pirate’s Alley Cafe, in an alley behind the St. Louis Cathedral, candlelit, open to the street. After a round, we moved on again, this time to Oceana, a restaurant where a table was being held for us through the web of connections people have when they have friends in the “service industry.” Many of the quarter’s streets were closed off to traffic and hordes of people were now pouring through the neighborhood, clutching plastic cups, the police visible on almost every corner, both NOPD and Louisiana State Police. Guess they really want this whole tourism thing to work out again. As we shouldered through the crowds I saw a white-haired woman confronting a white-haired couple. “You put me in this situation!”

At Oceana, our group of ten filed to an upstairs table. We were afflicted by a waiter who saw himself as a very amusing fellow. His phone rang while he was putting down cups of water. “That’s my agent! I must have got the part!” He recommended the crab cake and, when he heard that there were Marylanders in attendance, insisted that, if we didn’t think his crab cake was better than the Maryland version, “I’ll buy it.” The problem with the Maryland crab cake is that it’s “just crab – frankly, it’s kind of obnoxious,” he told us.

The waiter’s schtick included taking forever to even record our orders, a good tactic – from the waiter’s point of view – since it can result in more drink orders, and his tip for such a large party will be included in the bill anyway. But he was rarely around to take the drink orders anyway. “I think I’m sober again,” complained one guest. The room gave onto a wrought-iron balcony and the smokers and those of us who wanted to check out the view wandered back and forth through the rickety window. In the street below there was a Lucky hot dog cart, like the one staffed by Ignatius in Confederacy of Dunces.

Someone asked the waiter what else he does. Besides wait. “I run a youth hip-hop HIV prevention troupe,” he said, claiming to have performed all over the world. They wanted him so bad in Sydney, they put him on the Concorde to get him back in time for another show in Pittsburgh. “That was like an $8,000 seat,” he said. “And I just got in from Chicago on Tuesday.” Erin’s friend Courtney, who comes to Oceana “all the time” for the barbecued shrimp, said “he didn’t just get in on Tuesday. He’s been here a long time.” Crack use was alleged, though I couldn’t tell if this was a serious accusation or not. The waiter overhears that Erin and Greg will honeymoon in Costa Rica. “Beautiful place, you’ll love it,” he said. “I was there in – ” he scrunched up his face and thought ” – 1989. It’s so… tropical.”

The conversation takes some strange turns. “There are atmospheres where I like to see naked people, and atmospheres where I don’t.” “When I’m doing Primus on Guitar Hero, it’s like a special experience for me.”

Moving on from Oceana, we stop for takeout sweet mixed drinks from a sidewalk stand. The choice is between the Horny Gator, which comes in an alligator-shaped cup with two plastic green alligators balanced one atop the other (do I need to explain further?), “guaranteed to make you a better lover,” and the Hand Grenade, which comes with a little plastic hand grenade floating on the top and doesn’t seem to be guaranteed to do anything but give you a headache. I order a Hand Grenade and it is easily one of the most disgusting things I have ever tasted, at once too sugary but also lip-pursingly sour. At the first sip, I can feel a potential hangover awake in me, flexing its serpentine coils in the darkness, and so I drop it in a trash can as we pass through the gay section of Bourbon Street. (I noticed that, though the prospect of these drinks had been talked up quite a bit, almost none of the locals in the crowd we’re with actually buys one.) We’re headed for Lafitte’s, one of the oldest businesses – maybe even buildings – in the quarter, a blacksmith’s shop converted to a bar. It’s worth visiting on its own merits, says Erin, but the fact that the route to it passes the gay bars also plays a nice filtering role. “Most of the really dumb frat kids will just turn back when they see two guys kissing on the street.” “Yeah,” someone chimes in, “they’re afraid it might turn them gay, too.”

Our energy wanes, our sight grows dim. A. and I leave for our hotel and we are not the first to bail. It’s 1:30 a.m. by the time we are climbing into bed.

The next morning we learn that the bride and groom and their local friends outlasted us to the tune of three and a half more hours.